Walk through the research process and learn how to build a study step-by-step

Setting the Research Question

The initial step you must take is to identify a specific challenge or gap in your field of work (the research problem). After you identify the problem, you need to analyse the problem (e.g. the causes and the consequences of it) to justify the importance of conducting the research. This helps refine the framing of your research question. Examples of research questions you may ask are: 'Could a specific new hygiene practice reduce maternal deaths in rural health care settings in East Africa?' or 'Could sending informative text messages to nurses help them explain to HIV patients how to take their treatments?'

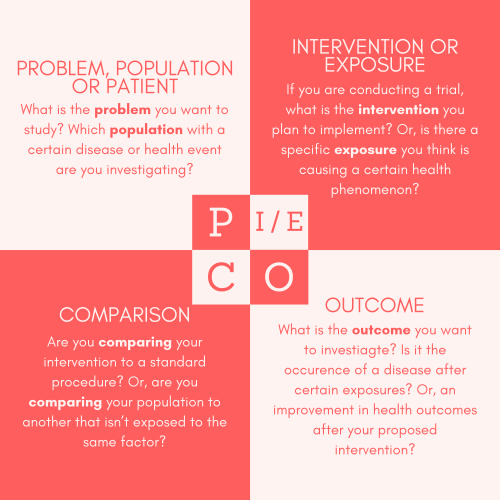

Having a clear research question helps you in various ways when developing your study – including narrowing down your data collection and analysis efforts to the essential points, and helping the reader understand what the objectives of your study are. A very helpful framework to guide you in formulating your research question is the PICO or PECO framework.

Figure 1: the PICO/PECO Framework.

Steps in Setting the Research Question

First Step: Identify Your Research Problem

The problem identification is the starting point. It is the recognition of a challenge, need or gap in knowledge.

Then, you may identify the causes of the problem and associated factors. This can be based on local knowledge, literature review, local or national priorities, or discussion with your research team.

It is important to identify the frequency, intensity, and geographical distribution of the problem to show the importance of addressing the problem.

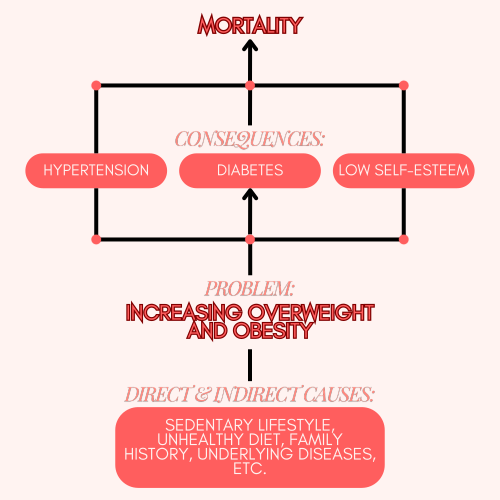

With this, we can construct the problem tree:

-

What is the central problem?

-

What is causing the problem?

-

What are the consequences or effects of that problem? This will justify why it is important to address the problem.

EXAMPLE:

|

Central problem |

Increasing overweight and obesity. |

|

Causes |

Multifactorial problem. Direct and indirect causes: sedentary lifestyle, diet, family history, underlying diseases. |

|

Consequences |

Hypertension, diabetes, decreased self-esteem, mortality. With information about them, you can justify why it is important to investigate, to propose a treatment to reduce the consequences. |

Figure 2: A problem tree example.

Second Step: Conduct Your Literature Review

What has already been done or what evidence is available regarding your proposed study?

A good and up-to-date literature review is essential to:

- Provide context, justification, and support for your research question

- Understand the extent of the problem

- Identify the causes and factors that influence the problem

- Identify the gap in the current literature landscape

Reading literature in your field allows you to stay on top of your game. If you're in a field you're interested in, this should not be too arduous.

The reading must go from the start to the end of the research process. If not, by the time you publish, there may already be a similar article published!

There are different types of literature, outlined below in Table 2:

Types of Literature

| Type | Where to find / Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Published | Manual searches, contacting researchers, database searches — high impact journals, PubMed, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, Scopus, SciELO, LILACS, etc. | The literature reviewers trust most; access depends on journal licenses. |

| Grey | Reports from governments, NGOs, industry, conference proceedings, theses, newsletters. | Not usually peer reviewed but useful for local context and framing the problem. |

| Unpublished | Expert interviews, conference participation, personal communications. | May provide timely insights not yet in the formal literature. |

Third Step: Set out your research aim, objectives, hypothesis and/or research question

Definition of Terms:

| TERM | DEFINITION |

|---|---|

| Research aim | A statement indicating the general aim or purpose of a research project. Usually one broad aim. |

| Research objectives | Specific statements indicating the key issues to be focused on in a research project. Usually several objectives. |

| Research questions | An alternative to research objectives where the key issues are stated as questions. |

| Research hypotheses | A prediction of a relationship between variables, usually predicting the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable. |

Study aim or overall objective:

- The overall objective of a study states what the researchers hope to achieve with the study in general terms.

- Objectives should be closely related to the problem statement. When evaluating the project, objectives are contrasted with results; if objectives are not clearly stated, the evaluation cannot be done.

Why should we formulate research objectives?

It will help you to:

- Focus the study (by narrowing it down to its essential points).

- Avoid collecting data that is not strictly necessary to understand and solve the problem you have identified.

- Organise the study into clearly defined parts or phases.

How should you set out your objectives?

- Ensure that they cover the different aspects of the problem and the contributing factors in a coherent and logically sequenced way.

- Make sure they are clearly stated in operational terms, specifying exactly what you are going to do, where, and for what purpose.

- Consider local conditions realistically.

- Use transitive verbs that are specific enough to evaluate. Examples: determine, compare, verify, calculate, describe, establish. Avoid intransitive verbs that do not express an evaluable action, such as appreciate, understand, or study.

Specific objectives:

- Specific objectives are quantifiable results at a specific time for the project. They are concrete measures to respond to the big question.

- List your specific objectives as a chronological sequence or logical flow: objective 1 / objective 2 / objective 3. Avoid listing activities that belong in the methods section.

- Research objectives can be descriptive, methodological (e.g., evaluating a lab technique), differential, or relational (e.g., comparing factors that influence X).

Keep in mind that not all research projects have hypotheses.

Example of a study's overall objective and specific objectives:

Objective: To assess the factors determining low adherence to the therapeutic regimen in patients who have received counselling and close monitoring in City X between July 2018 and July 2019.

Specific objectives: To determine:

- The number and proportion of patients with low adherence.

- The association between educational level and treatment adherence.

- The association between serious adverse effects and adherence to treatment.

- A good study comes down to setting a single and clear question — your primary objective — and then determining what you are going to measure in order to answer that question: your primary endpoint. Keep asking: “What is my question? Is what I am doing going to answer that question accurately?” Refer to the PICO or PECO Framework (Figure 1) to formulate your question.

Do you need more help? Please find links to more resources

- WWARN has a collection of literature reviews that provide valuable resources for researchers as they develop their clinical study programmes. These reviews help identify gaps in data, examine publication trends, consider different study approaches, and identify relevant clinical studies that may contribute results for pooled analyses (see WWARN study groups).

- WWARN Tools: monitor and track the emergence and spread of antimalarial resistance — find out more here.

- The process map: https://processmap.tghn.org/?mapnode=develop-research-question

- For additional support, you can access our free e-learning course: The Research Question — https://globalhealthtrainingcentre.tghn.org/elearning/education/elearning-courses/the-research-question/37/

- Protocol Development Toolkit: https://edctpknowledgehub.tghn.org/protocol-development/

Obtaining Permissions and Approvals

Are you undertaking a research study or an audit? What permissions do you need? It is research if you use information, take samples, or deliver any intervention (even new training) to a patient and intend to use the data for research where patients are identifiable and measurements are linked to individuals.

If you are doing research you will need: (1) a protocol, (2) ethics committee approval, and (3) consent from your institution. This is important so your findings can be taken up and shared. Whether research or an audit, you need permission within your workplace and possibly from the wider institution. There is help and support available.

How do you decide which permissions and approvals you need? Consider the following.

Key considerations

- Study population. Are the subjects real people (patients)? If so, you will usually need patient consent.

- Study setting / institution. If you recruit from hospitals, you will need ethical approval from those hospitals and possibly from your own institution.

- Obtaining permissions requires a research protocol so the institution can assess which parts require consent or approval.

Questions your protocol should answer

- What is the title of your study and who is involved?

- Provide a brief background of the problem you are addressing.

- Has other research addressed this problem?

- Why are you conducting this study? Is it novel?

- What questions will your study answer?

- Who will participate and where will the study take place?

- Is there an intervention or program to be implemented?

- What will you measure? Will you have before-and-after measures?

- How will you analyse the data you collect?

- Are there potential risks?

- Approximately how long will the study take?

There is more detail you can provide in a research protocol — the more transparent and detailed the better — but be concise. A typical protocol is no more than a few pages. Writing transparent protocols and following good ethics are key parts of good research practice.

Basic ethical principles

Many projects use an Ethics and Governance Framework. One example is the Ethics and Governance Framework of the International COVID-19 Data Alliance (ICODA).

- Deliver patient benefit: use data effectively in robust research and promote reporting of results.

- Foster equity: support LMIC-led research and recognise contributors to the data.

- Respect participants: honour data-sharing preferences and maintain community engagement.

- Protect privacy: ensure robust data security and manage access.

- Provide responsible stewardship: maintain transparency across all research activities.

If you have doubts or questions about ethics and institutional approval, check your national research ethics board. For a compiled list of country research ethics boards see: Country Research Ethics Boards (PDF) .

Your institution likely has its own ethics board — ask to meet them; they can answer questions about ethics and institutional approval.

Institutional approval & support

- Institutional review boards: Process map — institutional review boards

- You can find a template letter for institutional support via guidance and resources: Guidance & resources

Ethics approval

How to develop your protocol

- After completing the steps above you are ready to develop your study protocol.

- Protocol development guidance: Protocol development steps (EDCTP Knowledge Hub)

Developing Your Study Design

After identifying your research problem and formulating your research question and objectives, decide how you will answer your question: what data will you collect and how will you collect and measure it (what is your study design)? Will you use a survey, make clinical observations, or use an intervention? If so, which intervention — new training, a medicine, a diagnostic tool — or will you extract your answer from an existing dataset such as clinical records?

If your study includes human participants you also need to decide who your study participants will be (your study population: who you will include and exclude), and where your study will take place (hospital ward, outpatient clinic, participants' households, etc.).

What you're measuring in your study is usually the outcome; you'd like to see how your outcome differs based on the intervention your population received in comparison to some existing standard. Refer to the "Research Question" module for more details. Your population may help define your study setting (e.g., if your population is patients admitted to your hospital, the hospital is your study setting).

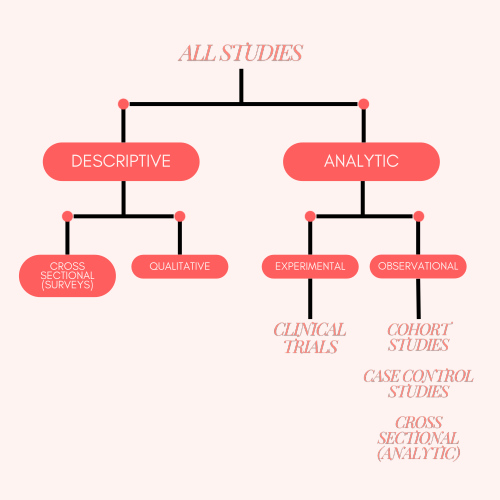

One of the first decisions is what sort of study design to undertake. Different study designs are better for different types of research questions.

- Descriptive studies — good for understanding the current state of things (e.g., current rates of handwashing in a clinic).

- Analytic studies — good for understanding how things change given an intervention (e.g., change in handwashing rates after putting up signs).

You can get more specific: within descriptive and analytic studies there are different types. The image below describes the different study types:

Figure 1: Types of study design

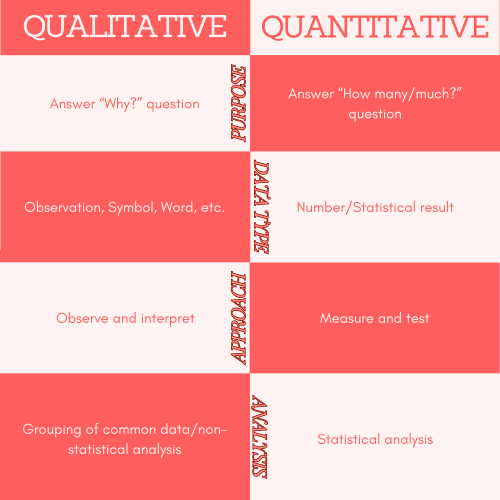

Now decide what it means to "measure" your outcomes. Do you want to measure outcomes as numbers (quantitative) or as descriptions (qualitative)? Numbers suit outcomes like weight or blood pressure; descriptive outcomes (e.g., knowledge of bandaging) may be best collected by interviews and assessed qualitatively.

https://www.simplypsychology.org/qualitative-quantitative.html

Having defined what you want to study, your target population, and the most appropriate study design, decide how you will study your target population. If your target population is all patients diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, it is impractical to include everyone; instead study a smaller group representative of the target population — this is sampling.

There are two broad sampling methods:

- Probability sampling — everyone in the target population has an equal chance of selection. This produces a representative sample and results that are generalisable.

- Non-probability sampling — participants are selected intentionally using specific criteria (not everyone has the same chance). More convenient but has limitations.

Do you need more help with this? Please find links to additional resources below

Data

Good data management is essential for ensuring the validity and quality of data in all types of research and is an essential precursor for data sharing. It includes how you collect, organise, store, and analyse your research data. This depends on the type of study you conducted (qualitative or quantitative), whether the data is primary or secondary, and the methods used to collect it.

Questions can include:

- What is the source of your data? Is it primary or secondary? Please elaborate.

- Which methods or tools will you use to collect the data? Please elaborate.

- How will you clean your data? What issues might arise during this process?

- Which method of analysis will you use, and why?

https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/resources/oima/cowi/data_management_handbook.html

Data collection

Data collection is gathering data relevant to answering your research questions and testing your hypothesis. Your study design determines your data collection methods and tools, as well as whether your data is quantitative or qualitative.

For quantitative studies, methods include surveys, closed-ended questionnaires, structured interviews, document review, sampling, and observation.

For qualitative studies, methods include surveys, open-ended questionnaires, in-depth interviews, and focus group discussions. These allow participants to express opinions, perspectives, and beliefs.

Data collection tools include checklists, questionnaires, interview guides, case studies, and forms. These may be administered on paper, online, or by phone.

Whichever tool or method you choose, ensure the results are reliable, valid, and reproducible so that your research is trustworthy and contributes meaningfully to the field.

Data organisation

After collecting your data, and before analysis, establish a system to organise it—especially when working in a team. Agree on procedures to avoid errors and save time.

Create folders organised by topic, and name files consistently. A common practice is appending dates to filenames for versions, such as “descriptives_work_20240516”.

Separate completed work from in-progress work. Always back up your folders to avoid data loss.

Reference management

While developing your study, you will consult published research. Reference management software helps you track, organise, and cite these sources correctly, and automatically produce bibliographies.

Common tools include EndNote, Zotero, and Mendeley.

Data cleaning and validation

Once data is collected, ensure quality before analysis. Data cleaning involves removing duplicates, correcting formatting issues, addressing missing or incorrect data, and removing irrelevant data. Validation is supported by selecting the correct study design and methodology.

Data analysis

After cleaning the data, identify patterns, trends, and correlations to answer your research question. How you analyse data depends on whether it is quantitative or qualitative.

Quantitative data

Descriptive analysis is used to measure prevalence or magnitude (e.g., prevalence of MDR TB or hospital infection rates).

Statistical analysis measures relationships between outcomes and exposures.

Examples:- Relationship between cervical cancer and smoking → univariate analysis (one independent variable).

- Relationship between cervical cancer and two factors (e.g., smoking and HPV) → multivariate analysis.

Various tools support quantitative analysis: SPSS, R, Stata, Excel, etc. Familiarity is key, though Excel has significant limitations and some journals do not accept Excel-based analyses.

Qualitative data

Analyse qualitative data by familiarising yourself with the content, then coding it (assigning interpretive labels).

Common approaches:

- Grounded theory analysis: coding occurs alongside data collection; themes emerge iteratively until saturation.

- Thematic analysis: coding starts after all data is collected, and themes are identified across the dataset.

- Framework analysis: themes and codes are predetermined; data is categorised into this framework.

Software options include NVivo and Dedoose.

Data storage

Tools such as Kobo and REDCap can store data securely. REDCap is institution-only; Kobo has a free limited version. Avoid tools like Google Forms for serious research, as they introduce complications (e.g., checkbox handling).

Best practice: follow institutional data-storage regulations. Ensure data is safe, secure, access-controlled, and not kept longer than recommended.

Secure storage also protects you if questions arise later about research integrity.

More help

- Global Health Data Science Knowledge Hub: https://globalhealthdatascience.tghn.org/

- Data Sharing Toolkit: https://edctpknowledgehub.tghn.org/data-sharing-toolkit/

- Data Management Portal: https://edctpknowledgehub.tghn.org/Dat-man-por/

- Data Sharing Training: https://globalhealthtrainingcentre.tghn.org/data-sharing/

Involving the Community in Your Study

The broad aim of community engagement is to enhance research by seeking consultation from relevant stakeholders.

Community engagement enables involvement and collaboration with affected communities, marginalised groups, and other key stakeholders in the design, implementation, and dissemination of research projects. Its importance has grown in recent years, as local communities are the ones most affected by the findings of your research.

Key stakeholders may include patients, caretakers, community members and leaders, faith groups, policymakers, civil society organisations, and non-governmental organisations.

Figure 1: What is community engagement? (Source: https://treattb.org/our-work/stream-trial/community-engagement )

Figure 2: Community engagement during research

Figure 3: The importance of community engagement

Figure 4: The 3 C’s model of participatory community engagement (1)

Do you want to learn more?

To learn more about community engagement, visit our community engagement hub (MESH): https://mesh.tghn.org/

References:

(1) Strengthening ethical community engagement in contemporary Malawi. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327731298_Strengthening_ethical_community_engagement_in_contemporary_Malawi [accessed Mar 22, 2024].

Dissemination and Implementation

Congratulations! You have your answer. Now, what are you going to do with this important new evidence? Will you generate new training methods or develop guidelines? Who do you need to work with — colleagues or policymakers? Please explain what you are going to do and share whatever you generate: training slides, policy briefs, toolkits, or even a short video explaining your findings and how others can implement them.

Tell us how you will take these findings back to the community where you did the study. Add this to the community engagement section so others can see how community engagement is an ongoing cycle that runs through the whole process. Share as much detail as possible — your experience will help others learn from your study and adapt the intervention in different care settings.

There are many ways your research can have impact. Some people write journal articles; others create toolkits. If your intervention improved outcomes, you might develop an implementation plan for other settings, draft a toolkit for testing in similar contexts, or prepare a policy paper with recommendations. Think about how to maximise the impact of your work.

Figure 1: What to do with research evidence

Ultimately, knowledge generation takes many forms. It's not just about turning your research into a scientific paper. It's about what benefits your community and best addresses the research problem. Use what you've created to build partnerships and further research opportunities.

More resources

- Research into Policy and Practice:

- Research impact:

- https://globalhealthtrainingcentre.tghn.org/articles/community-engagement-and-human-infrastructure-global-health-research/

- Research impact framework to guide research outputs: https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1472-6963-6-134

- How to write a scientific article:

How The Global Health Network Supports Career Development

The Global Health Network is transforming career opportunities for healthcare workers by making research skills accessible, practical and relevant to everyday practice. Many professionals wish to improve care through evidence, yet lack formal training or support to take part in research. Through free online courses, practical tools, communities of practice, regional activities and formal qualifications such as the Postgraduate Diploma in Global Health Research, the Network helps individuals gain confidence, develop new skills and progress in their careers.

Learning is grounded in real settings. A nurse can design a study for a local challenge. A midwife can strengthen community engagement. A laboratory scientist can improve data quality. A research manager can navigate ethics and regulation. As skills grow, so do opportunities. Many members begin with short courses, then join communities, use tools such as the Study Builder or Pathfinder, and later move into new research roles or pursue formal qualifications.

The videos below share these experiences first hand through the voices of healthcare workers.